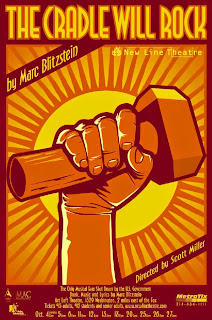

In 1999, Tim Robbins released a movie called Cradle Will Rock, about the legendary 1937 labor musical The Cradle Will Rock, a show at the center of one of the greatest theatre stories ever, the only musical ever shut down by the federal government. Cradle had music and text by Marc Blitzstein, and it was directed by Orson Welles and produced by John Houseman.

Interestingly, before he died, Orson Welles was trying to raise financing for a film about Cradle’s historic first performance. Here's the story:

After seeing Robbins' movie at the Tivoli back in 1999, I couldn't wait to work on this show. The movie had revised some of the pieces of the show we see, but they really get right the energy and wild joy of that famous night. It didn't take long for me to decide that New Line would do Cradle, like it happened on that historic opening night, with only Blitzstein on piano and the actors playing the whole show out in the audience, because their union had forbidden them to appear onstage.

We produced this piece of powerful meta-theatre in 2001, just a few weeks after the 9/11 attacks. And our audiences went crazy for it. Many of them even embraced their own role as 1937 audience members. (The program notes supplied their backstory for them.)

While we worked on Cradle, I read an excellent Blitzstein biography called Mark the Music, and discovered that Blitzstein wrote the most famous translation of The Threepenny Opera, the version that gave us the pop hit "Mack the Knife," the version that ran more than 2,700 performances off Broadway.

And now I'm finally directing Threepenny itself, in Blitzstein's excellent translation. So I decided to revisit Tim Robbins' movie, for some inspiration as we come down the home stretch. After all, Brecht appears in the movie, as a ghost in Blitzstein's head. And Robbins made a genuinely Brechtian movie, using lots of non-realistic devices to keep you at arm's length, while delivering an unmistakably political message at the center of his film, a message that seems remarkably relevant in 2015.

If you haven't seen the film, watch it. If you have, watch it again. It really is that good.

The film places the stage musical in a social and political context, but like the controversial musical Assassins, Robbins’ movie aims for thematic and psychological truth more than historical accuracy. In fact, the film begins with the words, “A (mostly) true story.” He plays fast and loose with a number of historical facts and brings together events that actually happened years apart, to reveal a larger context for Blitzstein’s remarkable musical. He uses the film conventions of the period to paint his pictures, the devices and styles of the screwball comedies of the 1930s, and the classic films of Frank Capra, Preston Sturges, and their contemporaries.

Robbins used the ghosts of Threepenny's author and lyricist, German director/

Similarly, though Blitzstein had harshly criticized the work of Brecht and composer Kurt Weill early in his career, he later came to admire their work and even emulate it. in fact, The Cradle Will Rock owes a great debt to Brecht and Weill, especially in its eventual bare-bones presentational style. Blitzstein actually met Brecht in 1936 and played for him the prostitute’s song from Cradle, “Nickel Under the Foot,” before any plans were made for the musical into which the song was eventually put. Brecht was impressed with the song and told Blitzstein that he should write a piece about all kinds of prostitution, not just the literal kind – the prostitution of the press, the church, the courts, the arts, government, money.

In Robbins' hands, this becomes a scene between Blitzstein and Brecht's ghost:

Brecht: What is your play about?

Blitzstein: What are your plays about? What is Threepenny Opera about?

Brecht: What is your play about?

Blitzstein: It's about a prostitute. It's about poverty.

Brecht: Survival? That is not enough. What about the other prostitutes? You don't have to be poor to be a whore...

The idea would percolate in Blitzstein’s brain for months before Brecht’s suggestion would inspire the creation of The Cradle Will Rock. Soon after that, Blitzstein heard Brecht and Weill’s song “Pirate Jenny” from Threepenny and he loved it. When Blitzstein wrote Cradle, he dedicated it to Brecht, and Blitzstein later wrote the most famous and most commercially successful English translation of Threepenny (the version New Line is doing). So it makes good dramatic sense in Robbins’ film, to dramatize Brecht’s influence by having his ghost hanging over Blitzstein’s shoulder, making suggestions, challenging him, ridiculing the cheap, easy moment, and pushing Blitzstein to be the best he can be.

Robbins also ties his movie to the Cradle stage musical thematically. The musical is about prostitution in various professions, the prostitution of the clergy, the press, artists, doctors, merchants, educators, and others, all set against the one actual prostitute, Moll, who is drawn with more integrity than any of the “respectable” characters. Robbins riffs on this theme by zooming in and focusing even more specifically on the prostitution of various kinds of artists. In the film, the painter Diego Rivera prostitutes himself to Nelson Rockefeller, the ventriloquist Tommy Crickshaw prostitutes himself by agreeing to tutor no-talent kids in exchange for a performing job, and the Italian Margherita Sarfatti prostitutes her national art treasures by selling masterpieces by Da Vinci and Michelangelo to rich Americans in order to finance Mussolini’s war machine.

One of Robbins’ most brilliant moves during filming of the movie was to save the shooting of the history-making, renegade Cradle performance until the end of the shooting schedule. Before starting, he explained to the audience of extras the background of the event, but did not tell them that the actors would be performing the show out in the house. Instead, he let the surprise of Olive Stanton rising to sing the first song register naturally on the audience. As the show proceeded, he just let the audience react naturally to each surprise and found that they laughed and cheered and applauded just as their 1937 counterparts did, sometimes in completely unexpected places. The incredible excitement of the evening built realistically and actor Hank Azaria (who played Blitzstein) said it was a night he will never forget.

The film works on so many levels all at once. For example, the opening shot of the film is one very long, uninterrupted shot that moves from inside a movie theatre, down a steep staircase, backwards through an alley out onto the street, up onto a crane that rises up to the second story window of Blitzstein's apartment, then in through the window, across the apartment to the piano, finally resting on a close-up of the sheet music Blitzstein is working on. But this isn't just a stunt or a joke, as it is at the beginning of another Tim Robbins’ movie The Player. There's a point being made here – the connection between the people on the street, the disenfranchised poor, and the social themes of Blitzstein's musical, between the popular entertainment of the movie theatre with Blitzstein's work; and also between the political events being shown in the movie theatre newsreel with the poverty of the everyday American on the street. Like Brecht and Weill, Blitzstein was writing a musical for the people, a musical of issues, a musical about the real world, and the opening shot of Robbins’ film shows us all those important connections in concrete terms.

Watching this beautiful, powerful film again, as we're thick in rehearsals for Threepenny, it becomes clearer to me than ever that Cradle – and Cabaret, Chicago, La Mancha, Bat Boy Urinetown, BBAJ, and so many other shows – all came from Threepenny. Brecht may have been German and a socialist, but he impacted the American musical theatre more than anyone else up to that point, with the exception of George M. Cohan.

The real miracle is how relevant both Threepenny and Cradle are in 2015. I don't know if that's testament to the shows' genius or to America's inability to fix the problems that persist decade after decade. Either way, both shows are in a very heightened style, but undeniably, aggressively realistic in their content. And we have much to learn from both shows...

We've moved into the theatre now, and we open in two weeks!

Long Live the Musical!

Scott

0 comments:

Post a Comment