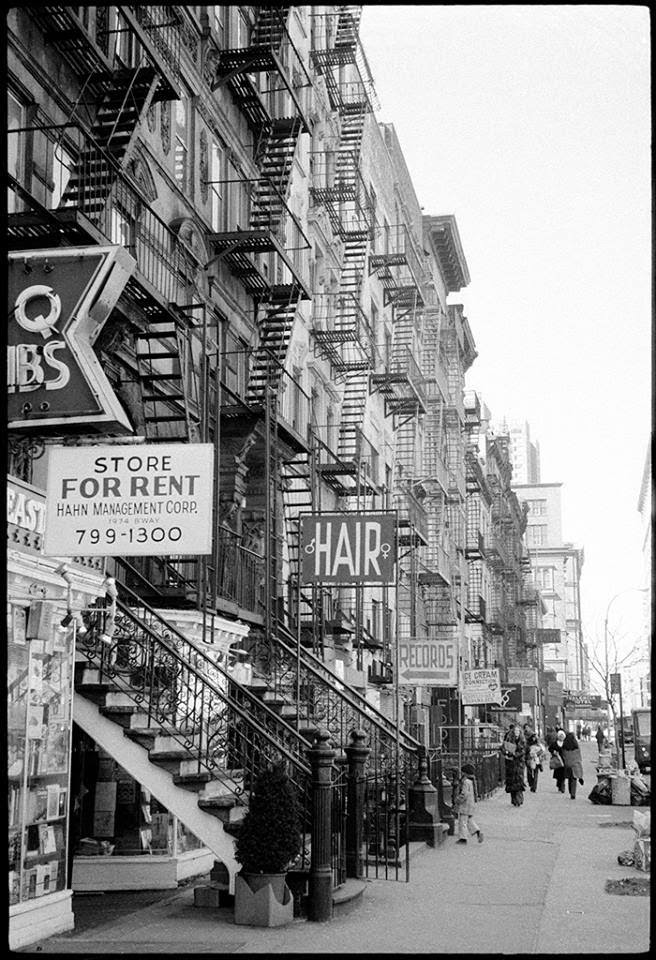

Cuban-American, queer director and playwright María Irene Fornés first discovered her deep love of theatre seeing a production of Samuel Beckett's absurdist masterpiece Waiting for Godot in Paris in 1954. She says it changed her life. A little more than ten years later, in 1965, she won an Obie Award for Distinguished Playwriting for two works in the same season, her musical Promenade and her play The Successful Life of 3. She won seven more Obies in the years since.

In Theatre and Literature of the Absurd, Michael Y. Bennett compares Fornés’ work with Beckett’s, writing, “Instead of two flat lines that comprise Act I and Act II of Waiting for Godot, her scenes, one after another, tend to have a rising action, but neither climax nor resolve; much like Godot, the audience is left hanging, but with Fornés, more on the edge of their seats.”

In a 1965 interview with Richard Shepard in The New York Times, Fornés said, “The play comes very deeply from my own consciousness. I didn’t sit down and figure out who were to be the characters. The explanation is an afterthought; there are images I believe in completely. . . Playwriting has less to do with language than novel writing does. It’s language in a very special way. Language is like the motor that starts a machine. How the machine performs, what dynamics it creates, that’s what counts.”

In a 1966 New York Post article, “Rebellion in the Arts,” critic Jerry Tallmer reported, “There were those who thought Promenade – an opera-farce of practically everything – was the best and funniest work in its season, off-off-Broadway or wherever.”

In 1969 Robert Pasolli wrote in the Village Voice, “Fornes’s minimal art says certainly not all, but something and something with implications for more. This is why her theatrical moments are delightful. Delight in her plays is simply the sensation of surprise that what seemed like nothing does, in fact, amount to something, sometimes to a great deal.”

In 1994, in a special section of the Performing Arts Journal devoted to the avant-garde, Fornes described her creative process to Bonnie Marranca, “I believe that there’s a creative system inside of us. It’s a system that’s almost physical. I can compare it with the digestive system or the respiratory system. . . The writing is not asking me for permission but it is taking force and just going.”

María Irene Fornés was called by some the Mother of the Avant Garde in 1960s New York. She wrote thirty-nine plays, and twenty of them have been published. Famed playwright Lanford Wilson said about Fornés, “She’s one of the very, very best – it’s a shame she’s always been performed in such obscurity. Her work has no precedents, it isn’t derived from anything. She’s the most original of us all.”

In his essay “Irene Fornés: The Elements of Style,” Village Voice critic Ross Wetzsteon writes, “From the first, her writing has involved a process of distillation, stripping away the behavioral and psychological conventions that pass for realism, and seeking instead a kind of hyperrealism (whether it appears in the guise of exuberant fantasy or severe documentation). And from the first, her plays have been formally shaped by an intuitive search not merely for a new theatrical vocabulary but for a new theatrical grammar.”

Her goal as a writer was to “catch” and surprise herself with what happens on the page, letting her subconscious and the simple logic of each moment take over. She never had a plan or a message or an agenda when she sat down to write. It was as natural and organic as she could make it.

To write Promenade, she made three piles of cards; one pile listing character types, one pile listing places; and one pile with a first line of dialogue. To begin writing the show she picked up two cards, “Aristocrats” from the character pile and “Prison” from the place file. How could she navigate that? Since Aristocrats can’t be in jail (or can they?), she began with two prisoners escaping from jail and encountering the Aristocrats.

Wetzsteon writes, “Fornés' trademark as a director is a gestural and informational formality, an emphasis on declamatory line reading in particular, that rejects the cumulative effect of naturalistic detail in favor of the spontaneous impact of revelatory image, that rejects emoting, behavioral verisimilitude, and demonstration of meaning in favor of crystallization, painterly blocking and layers of irony. The contrast, in many of Fornés’ plays, between the surface and the subtext helps account for their disorienting paradoxes: the simpler her work, the more mysterious its meanings, the more virulent the action, the more tender its feelings.”

“The Cigarette Song” in Promenade is just a random record of a tiny sliver of a life. In an interview, Fornés explained, “This really happened to me. One day I was walking down Fifth Avenue with a cigarette in one hand, a toothpick in the other, just thinking how wonderful it was to be able to sing when you wanted to, eat bread when you’re hungry. I grew up so poor in Cuba there weren’t even any breadlines – there wasn’t any bread. To be able to do all those wonderful things – that’s what that song means.”

Fornes never pulls her punches. She just shows us, no matter how ugly, no matter how trivial, no matter how maddeningly ambivalent. At the end of Promenade the prisoners’ mother (or is she?) sings a lullaby, but it’s not comforting, just disturbingly truthful.

I saw a man lying in the street

Asleep and drunk.

He had not washed his face.

He held his coat closed with a safety pin.

And I thought, and I thought,

Thank God, I’m better than he is.

Yes, thank God, I’m better than he.

And then the mother leaves her sons and sings to us, with brutal honesty:

I have to live with my own truth,

I have to live with it.

You live with your own truth.

I cannot live with it.

I have to live with my own truth.

Whether you like it or not.

Whether you like it or not.

At first blush, we accept this as a strong statement of individuality, but it’s a claim that we each have our own truth, so contradictory to others’ truths, that they can’t coexist. Good and evil don’t exist in the world of Promenade, because they would require consensus of definition, and there is no such thing.

So how did María Irene Fornés, decades ago, describe so accurately our current culture today in this new millennium, when what’s true is forever up for debate, and alternative facts are competing successfully with actual facts?

I know everything.

Half of it I really know,

The rest I make up,

The rest I make up.

Some things I’m sure of.

Of other things I’m too sure.

And of others I’m not sure at all.

Here at the end of the show, she turns her gaze on us in the audience, and she names our crime.

People believe everything they hear,

Not what they see,

Not what they see.

People believe everything they hear.

But me, I see everything.

Yes, I see everything.

Including her own obvious faults and failures as a member of society.

Wetzsteon ends his essay, “Fornés’ work is like a cross between Brecht and Midsummer Night’s Dream, with Eric von Stroheim and Gertrude Stein standing in the wings.”

In Fornés: Theatre in the Present, Dian Lynn Moroff writes, “The progress-less stories of Beckett’s theater also echo in Fornés’s theater. Her plays are rarely plot driven; more often, structure is the consequence of characters represented by their participation in small and frequently absurd scenes whose juxtapositions equal dramatic events. Fornes’s characters talk, pose, and posture incessantly, and Fornes’s theater lends significance to those ‘small’ acts with scrupulous theatrical framing; characters and audience alike are continually subjected to the carefully crafted and manipulated extraliterary spectacle of the body, light, music, color, and space. . . Her increasing emphasis on the gravity of role-playing, the character as determined by his or her context, and the slipperiness of language resurrect Jean Genet’s The Maids and Eugène Ionesco’s Rhinoceros. And lugubrious atmospheres conjure the dramas of the Irish lyrical playwrights William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory.”

Later in her book, Moroff writes, “Intimacy, pleasure, truthfulness, and an innocence willing to be taken by surprise – these are all crucial attributes of Fornés’s theatre.”

Stephen Bottoms writes in Playing Underground, “New plays like Irene Fornés’ Promenade, were defined not only by aesthetic innovation but by their immediate accessibility as entertainment.”

One of Fornés’ central concerns was the present-ness of theatre, that live actors are presenting this show to you right now in this moment, and the show they’ll present tomorrow will be a different one. Why is this? Fornés tells us in her lyrics “Once a moment passes, it never comes again.”

The adventure continues...

Long Live the Musical

Scott

P.S. To get your tickets for Promenade, click here.

P.P.S. To check out my newest musical theatre books, click here.

P.P.P.S. To donate to New Line Theatre, click here.