When I start blocking most shows, I have fully worked-out intellectual under-pinnings for all my choices. Sometimes, my fundamental approach to a show inherently contains those over-arching ideas -- our updated Jesus Christ Superstar was like that -- once I knew how I was coming at that show, most of the blocking choices were pretty obvious.

When I start blocking most shows, I have fully worked-out intellectual under-pinnings for all my choices. Sometimes, my fundamental approach to a show inherently contains those over-arching ideas -- our updated Jesus Christ Superstar was like that -- once I knew how I was coming at that show, most of the blocking choices were pretty obvious.The Wild Party is different. This time (as it was with Bat Boy, Love Kills, Return to the Forbidden Planet) I have a kind of instinctual understanding of what I'm doing, but I haven't been able to work it out intellectually yet...

When I was blocking Love Kills last fall, I started realizing that many of the scenes were very still, in some cases with both characters sitting the whole time and barely moving, or in the case of solos, with an actor just standing there singing to us. When I first noticed how still the show was, when I noticed how many big pauses we were using, I was a little concerned -- surely that's not how a rock musical works, is it? Well yes, it turns out, that's exactly how Love Kills works. The reactions from our audience, the critics, and the author told me my instincts were right. But I didn't fully understand why those were the right choices; they were counter-intuitive, but they just felt right.

The same is true of The Wild Party. I'm not sure I could justify all my choices, but they feel right. My gut seems to know how this show moves and looks, even if my brain hasn't caught up yet...

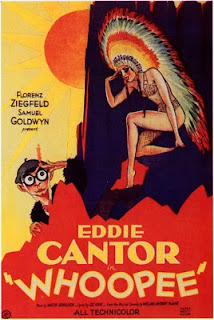

Tuesday night, after we blocked the middle of Act II (which involves only the four central characters), I realized that we're playing almost all the dialogue scenes pretty far down front, often with the actors standing in a line (or something close to it). But later, as I let it all swim around in my fevered brain on the drive home, I also realized that I'm giving the show the look of vaudeville and early musical comedy -- very downstage and very full-front. In both vaudeville and early musical comedy, a number of songs would always be sung in front of the closed main curtain, while they changed the set behind the curtain. I see now that, to an extent, I've staged a lot of this show as if I were a musical comedy director in 1928 (the year the Wild Party poem was published and the year we're setting our action), staging Whoopee!

Tuesday night, after we blocked the middle of Act II (which involves only the four central characters), I realized that we're playing almost all the dialogue scenes pretty far down front, often with the actors standing in a line (or something close to it). But later, as I let it all swim around in my fevered brain on the drive home, I also realized that I'm giving the show the look of vaudeville and early musical comedy -- very downstage and very full-front. In both vaudeville and early musical comedy, a number of songs would always be sung in front of the closed main curtain, while they changed the set behind the curtain. I see now that, to an extent, I've staged a lot of this show as if I were a musical comedy director in 1928 (the year the Wild Party poem was published and the year we're setting our action), staging Whoopee!Now, The Wild Party won't really work exactly like Whoopee because an audience in 2010 requires much more from their musicals than an audience in 1928 did (just a year after Show Boat opened, well before the Rodgers and Hammerstein revolution). The Wild Party operates, more than anything else, on the rules of Bertolt Brecht, but early musical comedy also operated (again, to some extent) on the rules of Brecht -- they just didn't know that's what they were doing.

I've always been a big fan of shows that acknowledge their own artificiality -- their theatre-ness -- shows that directly address the audience, that narrate, that step outside of scenes to comment, that admit every second that this is not real, that these are actors on a stage, that this is only storytelling. Almost every show New Line Theatre has ever produced fits that description -- The Rocky Horror Show, Bat Boy, Urinetown, High Fidelity, A New Brain, Return to the Forbidden Planet, The Robber Bridegroom, Reefer Madness, Floyd Collins, Assassins, and lots of others. In a way, The Wild Party simply has to be Brechtian, because Brecht's ideas are so close to the style of that period.

Brecht and Kurt Weill's landmark musical The Threepenny Opera would debut in Berlin in 1928 (what a coincidence!) and on Broadway in 1933. But it was originally a flop here, and it wouldn't be until the wildly popular 1954 off Broadway production that the show became famous in America and Brecht's ideas and practices would be consciously imitated on Broadway. Without the huge influence of that 1954 production, it's possible that we would have never gotten Company, Assassins, Urinetown, or Love Kills.

Brecht and Kurt Weill's landmark musical The Threepenny Opera would debut in Berlin in 1928 (what a coincidence!) and on Broadway in 1933. But it was originally a flop here, and it wouldn't be until the wildly popular 1954 off Broadway production that the show became famous in America and Brecht's ideas and practices would be consciously imitated on Broadway. Without the huge influence of that 1954 production, it's possible that we would have never gotten Company, Assassins, Urinetown, or Love Kills.Or, for that matter, The Wild Party.

All this is a little nerve-wracking because I don't "know" that I'm staging this show well, but I "feel" that I am. And as I've mentioned here before, this show is complex enough, that it will take a little time for the actors to find their way and to let the show find its footing. But while that's happening, I can't see exactly what my ideas will all look like. So I have to have faith that if I correctly figured out all our other shows for the past nineteen years, then I'm probably on the right track here too. But it does require me to have some faith -- in our cast, in myself, in the magic of theatre.

But that also means that the actors can't yet see what the end product will look like, so they have to have faith as well. I'm not sure most of the actors really understand how this show is going to look and move (although a few have already found the style), so they're just trusting me for now. The same thing happened with Urinetown -- if I remember right, it really wasn't until we got onstage that the actors "got" what we were going after. But god bless 'em, until that time, they trusted me and went on the ride I had set out for us. I can tell the same thing will happen this time.

We are so lucky to have a cast this good, this adventurous, and this trusting. This is a bigger adventure than most of our shows, but we've got the right team for the job.

Long Live the Musical!

Scott

0 comments:

Post a Comment