Happy Holidays from The Bad Boy of Musical Theatre! We're here again to help you find the perfect gift for that musical theatre fanboy or fangirl on your list who has everything! Tickets, calendars, books, and more!

Broadway Meets STL Rhythm, Passion, Style

Broadway Meets STL Rhythm, Passion, StyleFor two nights only, Jan. 9-10, the New Liners return to the acoustically magnificent Sheldon Concert Hall in the Grand Center Arts District. BROADWAY NOIR DEUX!, features a cast of all local actors of color, sharing with you a powerhouse celebration of Broadway musicals through the lens of their own lives, staking their claim to this most American art form, and reminding us that the Broadway musical belongs to all of us.

Click here to buy tickets.

Come

for the Party!

Come

for the Party! Stay for the War!

Don't miss your once-in-a-lifetime chance to see this uproarious experimental musical comedy from 1969! Beneath its dizzying comedy and catchy songs, PROMENADE follows the exploits of two escaped prisoners taking an unexpected tour of Capitalism and The Big City, where the poor and homeless mingle with the Idle Rich, exploring some big issues along the way, like wealth inequality, law and order, war, corruption, body image, gender, sexuality, and more.

Click here to buy tickets.

Will You Do the Fandango?

Will You Do the Fandango?New Line Theatre wraps up its 34th season with the global sensation, the electrifying rock adventure WE WILL ROCK YOU, a fantastical rock fable featuring 24 songs by QUEEN! Set in a futuristic, post-apocalyptic dystopia, WE WILL ROCK YOU follows two revolutionaries on their mission to save rock and roll. In an age where algorithms control our every choice, this musical is a rallying cry for our times, a fist-pumping, foot-stomping anthem to individuality.

Click here to buy tickets.

Bring Great Musical Theatre to our City!

Make a Year-End Donation to New Line!

Donate in the name of your favorite fanboy or fangirl. Donate in the memory of a loved one. Donate in honor of the teacher who turned you on to musicals. Donate in the name of your parents who drove you to rehearsals. Donate in Memory of Sondheim. Or just get an extra year-end tax deduction!

Just Click Here!

New Line Theatre is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

New

Line's 2025-26

New

Line's 2025-26Photo Calendar

Every year, we produce a wall calendar with high-quality photos from our shows by Jill Ritter Photography. Enjoy gorgeous production photos from some of New Line's coolest shows, Rocky Horror, American Idiot, Something Rotten, Dracula, Lizzie, Anything Goes, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Johnny Appleweed, Sweet Potato Queens, Return to the Forbidden Planet, and Jesus & Johnny Appleweed's Holy Rollin' Christmas!

The

Poster Art of

The

Poster Art ofNew Line Theatre

Yes that's right, we've published a coffee table book of all our posters over the last thirty-three years, all designed by St. Louis graphic artists Kris Wright, Matt Reedy, and others. It's a fun look back over New Line's amazing, unique history, and the company's first hundred shows. It's perfect for lovers of New Line and anyone who loves poster art, available now in hardcover and softcover editions.

New Line's "First Hundred Shows" Poster

New Line's "First Hundred Shows" PosterOne 36" x 24" poster that includes all the posters from New Line's first one hundred musicals (plus six Sheldon concerts). Get your Poster of Posters today!

New

Line Bumper Stickers

New

Line Bumper StickersCollect 'em all!

Go See a Musical;

Make Musicals, Not War;

got musicals?;

Bat Boy for Prez;

or the New Line logo.

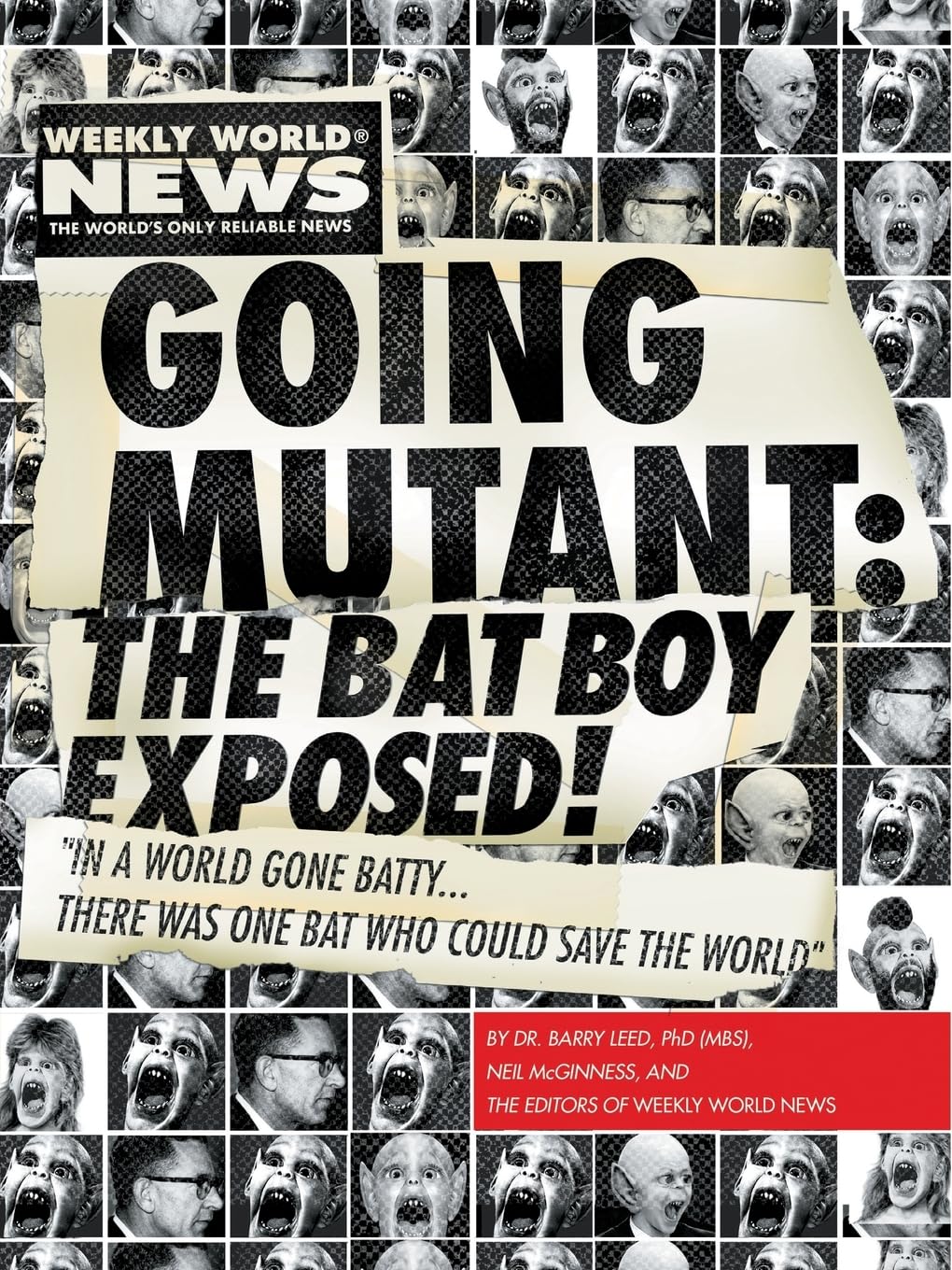

Bat

Boy

Bat

BoyYou loved seeing Bat Boy on our stage -- and we loved sharing it with you! Now you just can't get enough of him, right? No problem! We've got you covered.

Get ALL the Weekly World News articles about the Bat Boy, all in one crazy volume, Going Mutant!

Or how about a volume of the craziest WWN articles ever, Bat Boy Lives!

La Vie Boheme!

La Vie Boheme!the RENT novel

You saw Rent last season, but have you read the novel? People say the musical is based on the opera La Boheme, but it's much closer to Henri Murger's very funny, very truthful 1851 French novel about young artists, Scenes de la Vie de Boheme, now in an all-new, easier-to-read English translation! Every character from Rent has a parallel character in this original version of the story. Especially if you know Rent, you'll love this book!

Rocky Horror

Rocky HorrorOur audiences went crazy over our production of The Rocky Horror Show! For those of you who already knew the show, and for those who've just discovered it...

Get yourself the new 50th anniversary coffee table book, Rocky Horror: Featuring Unseen Photographs and Exclusive Interviews!

AND

Also the new Official Rocky Horror Late Night Double Feature: The 50th Anniversary Two-Volume Collector's Edition

The

Wonderful Music of BOZZ

The

Wonderful Music of BOZZThe new novel from Artistic Director Scott Miller, a fairy tale for the new millennium! In a dark world without music and without empathy, drama nerds Shellie and JoJo, and their new traveling companions, carry the fate of humankind on their artsy teenage shoulders. Can a musical save the world?

When L. Frank Baum first published The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, he wrote in his introduction, "The old time fairy tale, having served for generations, may now be classed as 'historical' in the children's library; for the time has come for a series of newer 'wonder tales' in which the stereotyped genie, dwarf and fairy are eliminated, together with all the horrible and blood-curdling incidents devised by their authors to point a fearsome moral to each tale." Baum wrote that in 1900. Miller thinks the time has come again.

JESUS & JOHNNY APPLEWEED'S HOLY ROLLIN' FAMILY CHRISTMAS

JESUS & JOHNNY APPLEWEED'S HOLY ROLLIN' FAMILY CHRISTMASYou loved this wild, vulgar, rowdy, outrageous, and hilarious musical satire in 2023. Now you can get the script and the vocal selections for yourself and for your nastier-minded friends!

“What if Seth Rogen, Charles Dickens, Andrew Lloyd Webber, Cheech and Chong, Christopher Hitchens, Hunter S. Thompson, and John Waters decided to have a baby?” – KDHX

"A pot-laced, Dickensian, Cheech & Chong-esque holiday spoof that is reminiscent of Saturday Night Live in its heyday." – BroadwayWorld

"A snarky (and oddly charming) holiday event." – TalkinBroadway

"Resembles the audacious dark comedy material that John Waters and Charles Busch specialize in." – PopLifeSTL

The ABCs of BROADWAY MUSICALS series

The ABCs of BROADWAY MUSICALS seriesThese terrific books from New Line artistic director Scott Miller are a series of fun, easy-to-read books, a totally not intimidating way to get a basic understanding of this most American of art forms, including a very brief history of musicals, a survey of important and well-known shows, examples of the wide and wild variety of musicals, a look at the amazing people who create musicals, and a sense of how Broadway musicals reflect and comment on our culture. You’ll never feel lost again in a conversation about musical theatre, and you’ll enjoy seeing musicals more than ever. These books are short enough to read in one sitting or you can flip open to any page and find something interesting. Even hardcore musical lovers may learn something from these little books! Now available -- The ABCs of Broadway Musicals; The ABCs of Acting in Musicals; The ABCs of Directing Musicals; and The ABCs of Writing Musicals.

REPRINTS!

So many interesting books and scripts have fallen into public domain lately, so it's possible to reprint them at long last. Here are just a few gems that are back in print after many decades out of print!

42nd Street, the novel

Go Into Your Dance, the novel

Stage Mother, the novel

Oh! James!, the novel that inspired No, No, Nanette

No No Nanette, the original 1925 script

The Fantasticks, the original play

Liliom, the play that inspired Carousel

A Day Well Spent, the play that inspired The Matchmaker and Hello, Dolly!

Sondheim & Grimm & Perrault, the original fairy tales that inspired Into the Woods

Twenty Years on Broadway, George M. Cohan's memoir

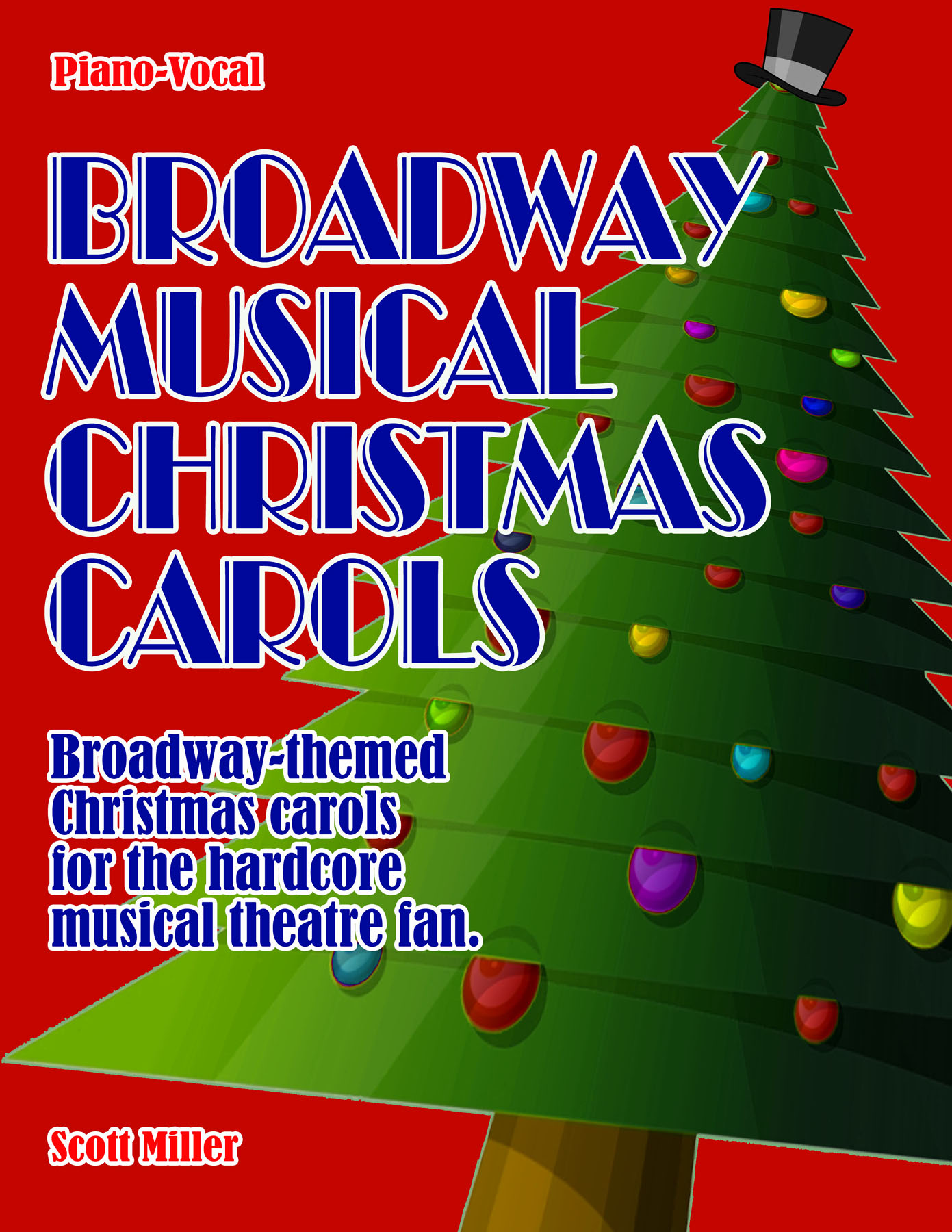

BROADWAY MUSICAL

BROADWAY MUSICALCHRISTMAS CAROLS

A piano-vocal songbook, full of 25 well-loved Christmas carols refashioned by Scott Miller for the hard-core fan of Broadway musicals, in new vocal arrangements with all-new lyrics related to musical theatre – funny, serious, smartass, cynical, reverent, poignant songs that will make you laugh, that will make you think, that will remind you why you love musicals so much.

The songs include “O Little Shop of Bethlehem,” “God Rest Ye, Mad Thenardiers,” “Away in a Mame Tour,” “I Heard You Screlt On Christmas Day,” “What Squip Is This,” “Here We Come A-Chorusing,” “O Come, All Ye Rent Heads,” “Jolly Old Steve Sondheim,” “Shrek, the Herald Angel, Sings,” “O Hamilton,” and other future classics.

ANYTHING,

ANYTHING, ANYTHING GOES! A Deep Dive

ANYTHING,

ANYTHING, ANYTHING GOES! A Deep DiveWe all get a kick out of Anything Goes. Find out why. One of the most performed musicals in history, Anything Goes has become a classic of the American theatre, and yet most people don't really understand the show and its wild mashup of musical comedy, screwball comedy, and gangster movies. Far from being an old-fashioned, old-school musical comedy, Anything Goes is a razor-sharp satire of America, as much about today as about the Thirties, the way we make celebrities out of criminals and make religion into show biz. It's irreverent, smartass, insightful, fearless, and very funny. Plus, it's got some of Cole Porter's best songs.

HE

NEVER DID ANYTHING TWICE

HE

NEVER DID ANYTHING TWICEGet ready for a mind-blowing trip through the Broadway musicals of the most fearless and influential artist in the history of the American musical theatre, Stephen Sondheim. Here are sixteen in-depth explorations of all the great Sondheim musicals, West Side Story, Gypsy, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Anyone Can Whistle, Evening Primrose, Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, The Frogs, Pacific Overtures, Sweeney Todd, Merrily We Roll Along, Sunday in the Park with George, Into the Woods, Assassins, and Passion; plus some brief stops at a few of his other musical and non-musical projects over the years.

GO GREASED LIGHTNING!

GO GREASED LIGHTNING!The Amazing Authenticity of Grease

So many people underestimate the intelligence and authenticity of Grease. So it’s time to set the record straight. Originally a rowdy, rebellious, piece of alternative theatre, written by two guys who really lived it, Grease was inspired by the rule-busting success of Hair, rejecting the happy trappings of Broadway for a more authentic, more visceral, more radical theatre experience. It’s an authentic snapshot of the end of the 1950s, a moment when the styles and culture of the disengaged and disenfranchised became overpowering symbols of teenage power and independence.

HAMILTON

AND THE NEW REVOLUTION:

HAMILTON

AND THE NEW REVOLUTION: Broadway Musicals in the 21st Century

How lucky we are to be alive right now! With this new volume, musical theatre scholar, director, historian, and fanboy Scott Miller takes you on a phantasmagorical journey through the second decade of this millennium, every stop along the way a Broadway musical truly like no other, all of them brilliant, original, and unique, all pointing toward an even brighter future for the art form and all the young artists creating amazing new work for us every day in this Golden Age for the musical theatre, including Hamilton, Dear Evan Hansen, A Strange Loop, Hadestown, The Color Purple, Bonnie & Clyde, Hands on a Hardbody, and The Scottsboro Boys, all shows that break the rules in smart, fearless, and surprising ways.

LET

THE SUN SHINE IN:

LET

THE SUN SHINE IN: The Genius of HAIR

In 1967, Hair launched a revolution. It rejected every convention of Broadway, of traditional theatre in general, and of the American musical specifically. It paved the way for the nonlinear concept musicals that dominated American musical theatre forever after. With more regional productions of Hair than ever before, Scott Miller gives us an incisive and fascinating analysis of the show. He looks at its place in theatre and cultural history, and its impact on recent musicals, including Rent. He delves into the mystical power Hair has over performers and viewers alike and its ability to literally change lives today -- including his.

RESCUING CATS:

RESCUING CATS: The Musical That's Better Than You Think

No matter how you approach it, Cats is so much more than a silly dance revue based on some silly poems, so much more than a punchline. Why has Cats been such a huge, longstanding commercial success around the world? Why do people see it over and over? Cats is literally about life and death. Cats is about us. Scott Miller takes another revelatory deep dive into this overly maligned but iconic musical, to see how it was made, what it's about, why it works, why so many people love it and so many people hate it. If you love Cats, you'll find here so much more to love. If you hate Cats, this book might just change your perspective a little.

SEX,

DRUGS, ROCK & ROLL, and MUSICALS

SEX,

DRUGS, ROCK & ROLL, and MUSICALSMore deep dives into ten musicals that engage with sex, drugs, and rock & roll in one way or another, from the artistic earthquake that was Hair to punk pop that is Hedwig and the Angry Inch. These are all shows that New Line has produced over the company's history, including The Wild Party, Grease, Hair, Jesus Christ Superstar, The Rocky Horror Show, The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, I Love My Wife, Bat Boy, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, and High Fidelity.

STRIKE

UP THE BAND

STRIKE

UP THE BANDThe whole history of musicals, pulling back the curtain on the amazing innovation and adventurousness of the art form, its political and social conscience, and its incredibly rapid evolution over the last century. Strike Up the Band focuses not only on what happened on stage but also on how, and why it matters to us today. Its a different kind of history that explores the famous and, especially, the not-so famous musicals to reveal the lineage that paved the way to contemporary musicals.

LITERALLY

ANYTHING GOES

LITERALLY

ANYTHING GOESAnother musical theatre book from Scott Miller that takes deep dives into more than a dozen incredible, quirky musicals spanning the history of our art form, all shows that New Line has produced, including The Threepenny Opera, Anything Goes, The Nervous Set, The Fantasticks, Zorbá, Two Gentlemen Of Verona, The Robber Bridegroom, Evita, Return to the Forbidden Planet, Kiss Of The Spider Woman, A New Brain, Reefer Madness, Bukowsical, and Love Kills. Nobody does deep, insightful, penetrating analysis of musicals like Miller does.

IDIOTS,

HEATHERS, and SQUIPS

IDIOTS,

HEATHERS, and SQUIPSIn this volume, Miller takes you on a short but fantastic journey through the first decade and a half of the new millennium, guided by deep dives into eleven of the musicals that represent the astonishing variety and fearlessness of this new Golden Age, including bare, Urinetown, Sweet Smell of Success, Jerry Springer the Opera, Passing Strange, Cry-Baby, Next to Normal, Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson, American Idiot, Heathers, and Be More Chill, all shows that opened in this new century, presented in chronological order so you can see how our art form is evolving like never before.

NIGHT

OF THE LIVING SHOW TUNES: 13 Tales of the Weird

NIGHT

OF THE LIVING SHOW TUNES: 13 Tales of the WeirdThe short story anthology that takes you on a roller coaster ride of thirteen nightmarish tales, all inspired in one way or another by the musical theatre, mashing together the history of musicals with the conventions and mad variety of the horror genre. You’ll meet theatre ghosts, vampires, monsters big and small, child killers, a homicidal maniac or two, a demon-possessed keyboard, and much more. The stories include "Tomorrow, Daddy," "Nothing More," "Night of the Festival," "Scarily We Roll Along," "Time Steps," "Requiem for Musical Comedy," "Happy Birthday, Robert," "I Had a Dream," "The Spellbinder," "A Little Fight Music," "The Farm Hand," "Over Finian’s Rainbow," and "The Flibbertijibbet." You’ll never think about musicals the same way again!

THE

ZOMBIES OF PENZANCE

THE

ZOMBIES OF PENZANCEYes, available now on Amazon, New Line's 2018 monster hit, The Zombies of Penzance, which the RFT called "a delightmare"! No more just a beloved if mildly unsettling memory, now you can bring those dancing and singing Zombies and Major-General Stanley's zombie hunting daughters all back to life -- death? -- with the Zombies of Penzance script, the full piano-vocal score, and the live original cast recording of the show, featuring the St. Louis cast and your favorite New Liners, recorded live in performance at the Marcelle Theater!

"A wonderful whirlwind of apocalyptic delight."

-- Tanya Seale, BroadwayWorld

Nominated for the American Theatre Critics Association's 2018 New Play Award!

THEATRE CATS:

THEATRE CATS: The Old Producer's Book of Dramatical Cats

In T.S. Eliot’s famous collection of poems, Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats, the basis for the megahit Andrew Lloyd Webber musical Cats, Eliot observed and made fun of the habits and behavior of everyday people, through the comic and insightful metaphor of some very human-like cats. In Scott Miller and Zachary Allen Farmer’s new collection, the targets are more specific but just as wickedly true-to-life, as Miller and Farmer explore the behavior of the quirky, eccentric, fascinating types who make musical theatre, this time through the lens of some very artsy cats, the good, the bad, and the finicky. And you can sing these new poems to the Lloyd Webber score...

SHELLIE

SHELBY SHARES THE

SHELLIE

SHELBY SHARES THESPOTLIGHT

The picture book you never knew you needed, in which Dr. Seuss meets 42nd Street, as freshman Shellie Shelby embarks on a wild adventure through the treacherous social jungle of her first high school musical. When Shellie gets cast in the school show, she can’t believe her luck, but her best friend, poor tone-deaf JoJo McQuill, isn’t so lucky. Can she successfully navigate the drama club mean girls, her crazy philosopher-teacher, music rehearsals, killer choreography, and Tech Week, without losing her mind and her best friend in the process? Written by Scott Miller, with original illustrations by longtime New Line Theatre actor Zachary Allen Farmer.

That's it -- your 2025 Gift Guide. We hope it's helpful. And we hope your holidays are good ones, that lots of wonderful art comes into your life, and that you join us in 2026 for some more truly wonderful shows!

Happy Holidays!

Long Live the Musical!

Scott

P.S. Stay tuned -- on New Year's Eve, I'll post my 12th annual year-end poem looking back on The Year in New Line!