And maybe more to the point, what value does a theatre review have today, when literally anyone can set up a blog and declare themselves a reviewer? Like filmmaking, music, publishing, and other areas, reviewing has been radically democratized in this digital age. Anyone can make a film now, or record a song, or publish a book.

And anyone can be a reviewer. Literally.

That's because there are no criteria to be a reviewer, no gatekeepers, no particular rules or conventions or deadlines anymore -- and no editors! -- so reviews are now just random people's opinions, quite often people with no training, expertise, or credentials. Just opinions. And many reviewers take a week or two (or more) to publish their reviews, giving them even less value. Theatre reviews are fast becoming little more than Amazon customer reviews. And I guess that's not necessarily a problem -- as long as we understand that's what they are.

Throughout the 32-year history of New Line, I have publicly called out reviewers when they weren't doing their jobs. I won't go after them if they simply don't like a show, but I will if they misunderstand the show and then criticize it for their misunderstanding, or if their review is simplistic and superficial. Especially in New Line's early days, too many people still thought all musicals are silly and brainless, and I had to teach reviewers how to watch and think about the work we do.

Sometimes, local actors and directors are horrified that I dare review the reviewer. But why shouldn't we?

When New Line produced Jerry Springer the Opera, one local reviewer ended his review by telling his readers that they might enjoy the show more if they left fifteen minutes before the end, because nothing happens. Now the truth is, the last fifteen minutes of the show are very intellectually dense and philosophical, referencing Dante and William Blake, and ultimately leaving us with a profound statement that lines up shockingly well with the ethos of Springer's TV show. By the end of this brilliant opera, Jerry Springer himself has united Heaven and Hell.

In other words, there's a lot that happens in the last fifteen minutes of the show, and this reviewer just didn't understand any of it. I called him out on it.

When we produced The Rocky Horror Show the first time, one reviewer dismissed our production entirely because it wasn't enough like the film. But we weren't producing the film. We were producing the very different stage show, which came first. I called him out on it.

When we produced The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, one reviewer dismissed the entire show as "glamorizing" prostitution. But onstage (unlike the film), Whorehouse is a very clear-eyed look at prostitution, and it tells a true story, with a very unhappy, true ending. And besides, the stage show isn't about sex or about prostitution -- it's about the mad hypocrisy of the culture and politics around these women, at the height of the Sexual Revolution. And seriously, how glamorous could they be when they're all wearing early 1970s polyester jumpsuits? I called the reviewer out on it.

So when we got a positive but clownish review from KDHX for our current production of American Idiot, I called the reviewer out on it. On cue, a handful of local actors were predictably shocked, stunned, and deeply saddened yet again that I had reviewed the reviewer. Apparently, they believe reviewers can criticize our work, even irresponsibly, but their work deserves some kind of Trumpian Immunity?

No.

In this Idiot review, the first two paragraphs are the reviewer's pointless musical autobiography, weirdly straining to establish his punk street cred. (Spoiler Alert: reviews are not about the reviewers.)

When he finally gets to the show he's reviewing, he declares that "New Line's timing" in producing the show this year is "well-timed." Our timing is well-timed? (KDHX has since fixed this sentence, so clearly somebody knows there's a problem here.)

Then this guy writes, "Despite its obvious six degrees of plot separation from La Bohème by way of Hair and Rent...” What's he smoking? The plot, characters, and themes of American Idiot have virtually nothing to do with Bohème, Hair or Rent. And also, how do you play the Six Degrees game with plots?

He goes on to write, "The musicians sit behind a chain link fence, but their musical talents, under the direction of bassist John Gerdes, roam freely..." WTF? Can someone please explain to me how musical talents roam freely...? This is a reviewer who loves his own writing too much and who's trying to sound like a better writer than he is. That never works. And also, reviews are not about the reviewers.

There's lots more clumsy self-indulgence in this review, but I'll spare you. What's my point? The artists who work with New Line deserve better. This kind of chatty, un-serious review is disrespectful of us and our work.

As I expected, I was social-media-scolded for being a bully and for having a "meltdown," for reviewing this guy's review. Let's get real -- disagreeing is not bullying, despite what people on Facebook may think. And being offended is not having a meltdown. I'm baffled by this genuinely weird mindset that reviewers are somehow above review, that it's "unprofessional" to call them out.

Because that would mean that Steve Sondheim, Hal Prince, David Merrick, Joe Papp, and lots of other legendary theatre artists have been unprofessional for publicly calling out critics for irresponsible reviews. (They haven't.) If reviewers want to be part of the public cultural conversation, they have to take the good with the bad, like everyone else who puts work before the public.

You know, like theatre artists.

Reviewers should not get a pass for un-serious, un-thoughtful reviews. In Days of Olde (pre-internet), reviewers were afforded some respect and authority because their job was to think and write about the art form, and even so, they were often held to account by the public through Letters to the Editor. But that's nobody's job anymore, at least not in St. Louis. Nobody gets paid to review theatre locally. Now, reviewing is a sideline. A hobby. Some of our local reviewers are excellent, some are fine, but a few are terrible and a few are little more than synopsis machines. One big problem is that admission to the Critical Community is now just the price of setting up a free blog.

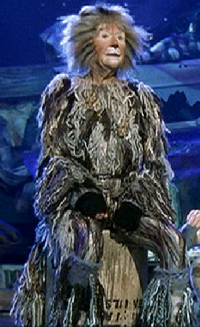

To paraphrase Gus the Theatre Cat, "Reviewing is certainly not what it was." It's probably too much to ask that any of them read any of these...

How to Write About Theatre: A Manual for Critics, Students, and Bloggers

The Critics Say: 57 Theatre Reviewers in New York and Beyond Discuss Their Craft and Its Future

The Art of Writing for the Theatre: An Introduction to Script Analysis, Criticism, and Playwriting

The Critics Canon: Standard of Theatrical Reviewing in America

So what do we do about all this? No idea. As a species, we're still figuring out how to navigate the digital era, how to sift out the bullshit from the truth, who to give our trust to, who to believe, how to judge information, and so much more.

Maybe in this digital information age, when theatre companies can share with their potential audience (virtually cost-free) production photos, rehearsal photos, video clips, glimpses behind-the-scenes, interviews, blog diaries, and so much more -- maybe reviews as we know them and review pull-quotes will soon go the way of the Betamax and the Walkman.

I mean, when many reviews have all the gravitas and depth of a Facebook post, do we really need them? Do they still serve the community in any meaningful way?

Reviewers in St. Louis don't represent theatre audiences today the way they once might have. To be blunt, with only a couple exceptions, all the St. Louis reviewers are pretty old; the majority are male; and with only the rarest exception, they're all white. That does not align with the majority of our audience. Or the audiences we want to reach. Or our city.

So now what? No idea. It's a new world. And there's still a lot to figure out.

Long Live the Musical!

Scott

Author's Note: I generally distinguish between critics, who write about shows in the context of the art form and the times and the culture; and reviewers, who say if they liked a show or not. Critics are people like George Bernard Shaw, Harley Granville-Barker, Eric Bentley, George Jean Nathan, Harold Clurman, Langston Hughes, Robert Brustein, Frank Rich, George C. Wolfe, et al.

P.S. To buy American Idiot tickets, click here.

P.P.S. To check out my newest musical theatre books, click here.

P.P.P.S. To donate to New Line Theatre, click here

0 comments:

Post a Comment