(An excerpt from my new book Rescuing Cats: The Musical That's Better Than You Think)

I’m a musical theatre snob.

I admit it. I just don’t enjoy a mediocre, conventional musical anymore – or even worse, a mindlessly conventional production of a rich, complex, unconventional musical. But I’m no knee-jerk snob. It’s just that I love what’s amazing. And truthfully, there’s a lot of it.

While it’s true that many of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s later shows are not my cup o’ tea, I honestly think that Jesus Christ Superstar is a brilliant, audacious piece of musical storytelling that is too often treated like a shallow church pageant. (Spoiler Alert: It’s not.) And I think that Evita is a masterwork, in fact, much richer, more nuanced than Hal Prince’s original production and Patti LuPone’s original performance led us to believe (as much as I revere Hal Prince and La LuPone). Evita is a dark, morally complex, seductively charming, double love story; it’s not a Brechtian horror show about an ice queen.

And I will also admit I love Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat. No, it’s not a masterwork. But let’s be honest, it’s relentlessly clever, endearingly smartass, and it’s chock full of catchy songs. Hating on Joseph is like hating on Hello, Dolly! And while we’re here, I’ll also admit I really love Song and Dance. The first half of that show, the one-act Tell Me on a Sunday is a serious, complicated character study of a deeply damaged woman who has no self-awareness; that’s tricky to dramatize, but the show really works. And the music for the second half of Song and Dance, Lloyd Webber’s “Variations” for cello, is one of my favorite pieces of instrumental music. It’s so inventive, so playful, and it does what Lloyd Webber does best, straddling confidently the worlds and vocabularies of classical music, pop, jazz, and theatre music.

And then there’s Cats.

It seems so easy to make fun of it, parody it, “pee on it,” so to speak. Everybody seems to love it or hate it, and both positions often seem irrational to me. (Then again, how someone responds to a piece of art is subjective, right?) Maybe it’s the strangely intense vitriol, the passionate, enraged loathing of this musical, that all seems so weird to me. It’s like people are mad at the whole idea of the show, which again is baffling. It’s just a musical, after all. No one is claiming it’s the next Dianetics.

I first encountered the show through the Broadway cast recording (on LP!), right after it was released, and I fell in love with the score. The lyrics revealed more depth and more comic ambiguity each time I listened to them – and more humanity – in their wonderful mashup of real cat behavior mixed with hilariously real human personalities. I’ve never understood why some people hate Cats so fiercely.

Not long ago, I got the idea to write a book of poems modeled on Eliot’s cat poems; but while Eliot lovingly satirized human behavior through the comic lens of cat behavior, my book, Theatre Cats: The Old Producer’s Book of Dramatical Cats, lovingly satirizes the behavior of theatre people, through the lens of some unusually artsy cats. Writing these pieces was fun for me on several levels, and it gave me a much deeper appreciation for everything Eliot did in those original poems. I also wrote a short story, “Night of the Festival,” for my Weird Fiction anthology, Night of the Living Show Tunes, in which the narrator wakes up at the Jellicle Ball transformed into a cat, and he slowly loses his humanity as he becomes part of the ritual. Again, it was a fun project that got me thinking about the musical in new ways.

John Rockwell wrote about Lloyd Webber in The New York Times in 1987, “Depending upon your source, the following passionately held opinions will be proffered at the mere mention of his name: He is the savior and regenerator of the very genre of the musical. He is the pioneer of the rock musical. He is a barely disguised opera composer. More than anyone, he has tipped the musical's creative locus from New York to London. He is the instigator of the current penchant for glitzy spectacle on Broadway. He is a composer of melodic genius and telling theatrical savvy. He is a cheap panderer to the lowest common denominator, derivative and faceless.”

Many critics predicted the only real appeal of Cats would be the spectacle, the show-bizzy glitz and eye candy. But that’s simply not true. People don’t go to the theatre for eye candy; they go for connection. Through these poems, T.S. Eliot created this crazy, vaguely familiar universe that is both our human world and a secret cat world at the same time, occupying the same space, living with all the same moral ambiguities. These characters and their stories all exist in this fantastical double-reality. And part of the “running joke” (if I can apply that term to T.S. Eliot) is our unavoidable awareness that while this isn’t our Real World, it sure reveals our Real World – and us – to us.

But it wasn’t just Eliot’s text that grabbed me. Andrew Lloyd Webber’s music for Cats is so playful, and in real ways reflects both the sly, satirical humor of Eliot’s text and also a fully alternate cat world, where musical styles leap from one to another, songs gets interrupted, melodies cavort, and rhythms behave as erratically as cats.

The wild 13/8 time signature of “Skimbleshanks” (breathlessly counted 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2, 1-2) gives us a palpable sense of movement, energy, busyness, painting a rich aural portrait of Skimbleshanks’ workplace. In a similar manner, the constantly shifting, irregular time signatures of “Memory” echo Grizabella’s scattered, broken thoughts. There are examples like this throughout the Cats score. We already knew that Lloyd Webber has an extraordinary gift for melody, but the bonus here is the beautiful melodies even in the instrumental music, not just the usual reworkings of the vocal melody, but often entirely new themes, as in “The Gumbie Cat” dance break.

Rockwell wrote in that same New York Times article, “What Lloyd Webber achieved was the expansion of the musical-theater composer's resources to include rock, at a time when most American writers for the musical theater continued to resist it. Born into the rock era, he was, along with Tim Rice, a true pop fan, and found it both natural and necessary to use rock music in a theatrical context.” He went on, “It was Cats that was Lloyd Webber's real declaration of independence from Rice – the partnership had dissolved after Evita, the victim of a mounting friction of egos – as well as his first project to make him real money. It is the key musical in his career, the show that defined him on his own, established the very idea of a new English musical and crystallized the controversy that has swirled around him ever since.”

Some people complain that Cats doesn’t have a plot. They are wrong. It has a narrative story, with a beginning, middle, and end, centered on the choice of the cat to go to the Heaviside Layer at the end. The show even observes Aristotle’s dramatic unities, of time, place, and action.

Though most of the time theatre tells us linear narrative stories – that’s what we’re used to – theatre is also about ritual. And while Cats does tell us a linear story, it’s even more about the sacred ritual behind that story. T.S. Eliot famously wrote in a review in 1923, “All art emulates the condition of ritual. That is what it comes from and to that it must return for nourishment.” Eliot always felt a strong obligation to tradition, to culture and heritage, and ritual was always a part of that. Significantly, throughout history and still today most religious services closely resemble theatre performances, both in the physical space (with “stage” and “audience”) and in the structure of the content.

But almost everyone has misunderstood Cats from the start, trying to cram it into preexisting categories and conventions and styles. Cats is musical theatre as ritual. It’s not a revue. It’s not a song cycle.

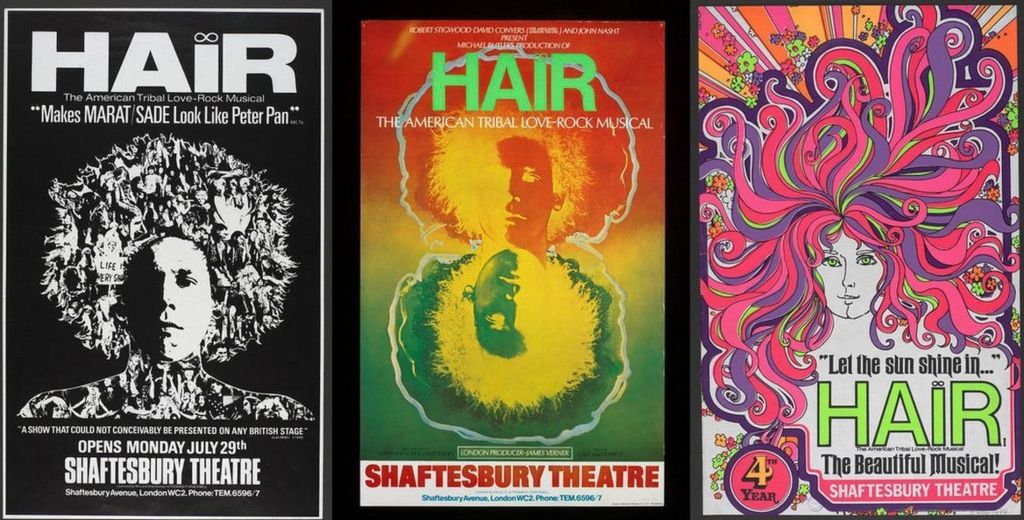

Cats is very much like Hair. Yet the critics and the musical theatre snobs forever yammer on about how it’s all production design and no plot, or has only “a thin plot.” The truth is that just like Hair has a linear dramatic throughline, so does Cats. Just as any ritual does. Hair, Celebration, and Godspell all experimented with ritual as musical theatre, all three in different ways, and later, The Gospel at Colonus did too. And that’s what Cats is, a ritual, beginning with the summoning and gathering of the tribe. This community of individuals isn’t here to tell us a story this time; they’re here to remind themselves – and us – who we are.

One of the things that drew me to Cats was that I knew these personality types – the clueless snob, the bully, the rock and roll rebel, the passive-aggressive control freak, the shit disturbers, the faded beauty. Eliot’s great stunt was illuminating with loving insight some truths about human behavior, through the shockingly sharp lens of observed cat behavior. But that was only half his trick. The other half was allowing us to see, to our delight, where the two intertwine and overlap.

I love this show. Here’s why.

Long Live the Musical!

Scott

To buy your New Line season tickets for next season, click here.

To donate to New Line Theatre, click here.

To check out my newest musical theatre books, including my latest, He Never Did Anything Twice: Deconstructing Stephen Sondheim and Rescuing Cats, click here.

No comments:

Post a Comment